Every egg rolls a different way. For centuries, scientists wondered why egg shapes are so different from one bird to the next. Now, we think we’ve finally cracked the mystery.

To start, we need to know what egg shapes are even possible. Luckily, hobbyists and natural history museums have been collecting and cataloging bird eggs for hundreds of years. Then, what kind of birds are linked with the different shapes? And finally, how might their special traits—from nesting habits to body size—change the shape of their eggs over evolutionary time?

Spherical

Owl

Elliptical

Maleo

Conical

Murre

Represents 100 eggs

Extracting the data

Scientists started their quest by looking at photographs of 49,175 bird eggs collected from nests, burrows, and colonies all over the world for more than 100 years.

Each photograph—supplied by the The Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at Berkeley—has two key elements: an egg (or eggs) and a ruler. The team used a special computer program to scan each picture, get the egg measurements, and then figure out the complete range of egg shapes in birds. They collected pictures from 37 bird orders. That’s all of the major bird orders.

1400 species

That’s 14% of all 10,000 bird species.

Spherical

1 cm

Grading the eggs

Ellipticity

Asymmetry

A motley crew

Next, researchers looked at two features: asymmetry, or how pointy the eggs are, and ellipticity, or how much the eggs deviate from a perfect sphere.

Eggs are all over the place. Some are elliptical. Some are asymmetrical. Some are both at the same time. And some—like the perfect sphere of the hawk-owl—are neither.

Egg extremes

The hawk-owl has the most spherical egg. But other birds are off the charts, too. Shorebirds like the murre and sandpiper produce super asymmetrical eggs. The murre’s egg is also one of the most elliptical.

A happy medium

The most common kind of egg is like that of the graceful prinia (Prinia gracilis)—not quite the chicken egg most of us conjure up when thinking about egg shape.

Elliptical

1 cm

Cracking the case

Over the years, bird lovers and scientists have come up with all sorts of hypotheses for egg shape—most are related to the life history of the bird or the environment in which they live.

Clutch size

The number of eggs in a clutch could influence egg appearance, with some shapes optimized for sharing the warmth.

Calcium conservation

Spherical eggs have less surface area, which could help conserve calcium in places where the mineral is rare.

The roll factor

Spherical eggs could easily roll off a cliff. Conical eggs, however, roll in a tight circle, making them perfect for cliff-nesting birds.

In addition to these theories, scientists also thought that precocial baby birds—those that are usually mobile and more mature at birth, like ducks—had asymmetrical eggs because the blunt ends have more pores, letting in more oxygen to help their brains develop faster.

Researchers put all these theories to the test by looking at the life histories and the evolutionary relationships of the birds in a new study, published in Science.

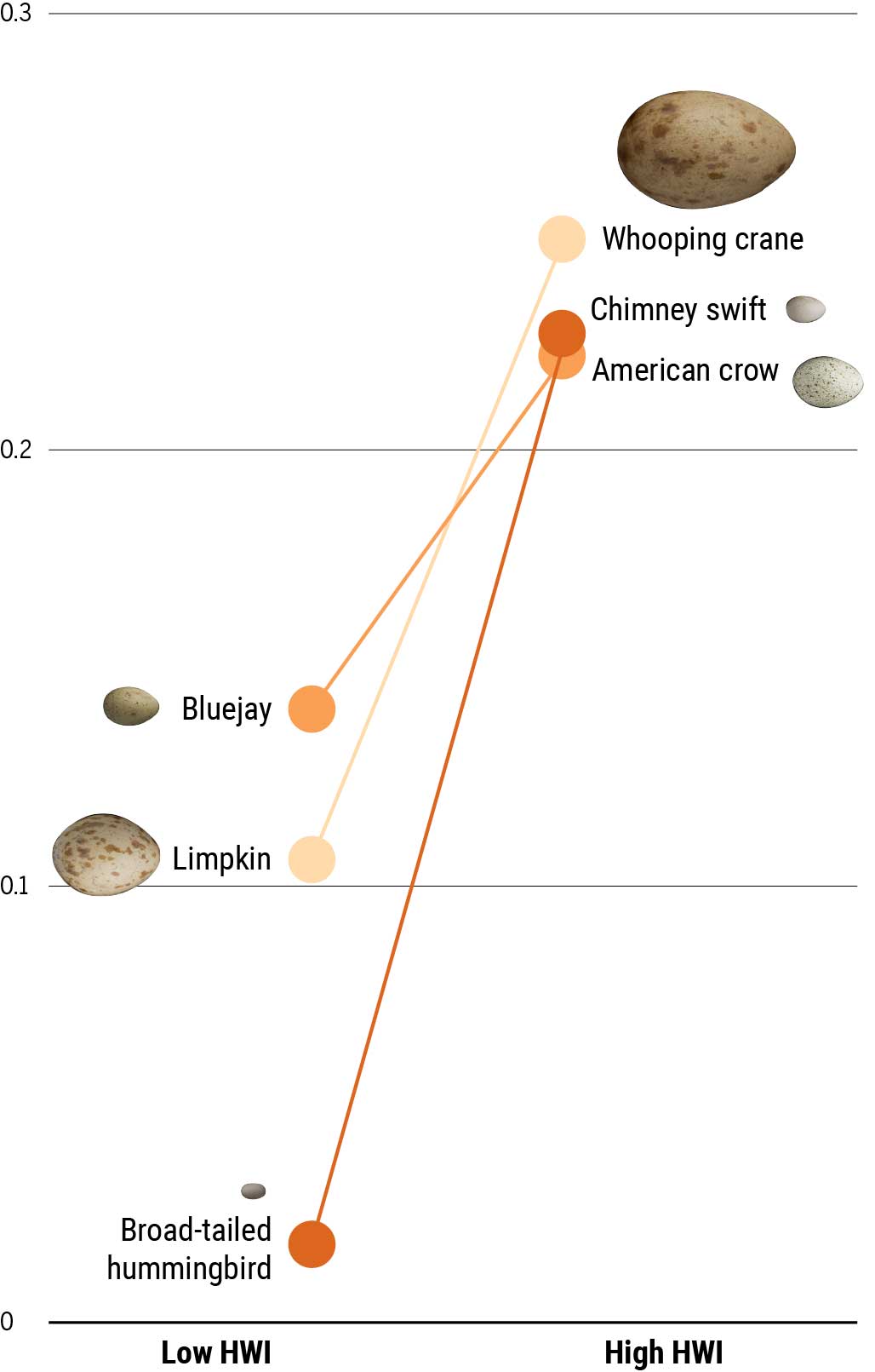

They looked at a whole slew of variables, including: adult body mass; diet; number of eggs in a nest; nest type; nest location; environment; and something called hand-wing index (HWI), a proxy for flight capability. A high HWI is linked to better flight performance.

After crunching the numbers, the scientists found the links they’d been looking for: the length of an egg correlates with bird body size. The shape of an egg—how asymmetrical or elliptical it is—relates to flying habits. And the stronger a bird's flight, the more asymmetrical or elliptical its eggs will be.

Degree of asymmetry

When looking at birds in the same order, those with stronger flight tend to have eggs that are more asymmetrical.

Degree of ellipticity

When looking at birds in the same order, those with stronger flight tend to have eggs that are more elliptical.

Conical

1 cm

Building the perfect egg

What’s the link between flying and egg shape? Birds have a streamlined body plan, and—especially in stronger fliers—their organs are squashed and minimized.

In order to get the most out of (or into) their eggs, strong fliers make them with asymmetrical or elliptical shapes—which have more volume, relative to their girth, than perfectly spherical eggs.

What actually shapes the egg? One obvious factor is the size of the mother bird’s oviduct. But it also turns out that egg shape is a balance between two pressures—from the contents inside the egg and from the oviduct outside, moderated by the thickness of the egg membrane right under the shell—not the shell itself. (Fun fact: If you carefully remove the shell from the membrane, an egg will still retain its shape.).

Scientists made a model with these variables, using real-life data on membrane thickness. After they ran the numbers, they were able to “conceive” a chicken egg from scratch.

The relationship between flying ability and egg shape does have exceptions, though. For example, whereas ostrich eggs tend to be spherical, kiwi eggs are elliptical—even though both species don’t fly. Flightless penguins also lay asymmetrical eggs, which researchers pin on their streamlined body plans, designed for powerful underwater swimming.

Now that scientists are finally starting to make sense of egg shape, perhaps it’s time they move on to more pressing matters of the chicken-and-egg variety: For example, which came first?

Producers: Jia You, Sarah Crespi Supervising producers: Alberto Cuadra, Beth Rakouskas Video: Nguyen Khoi Nguyen Design, graphics, and animation: Alberto Cuadra, Garvin Grullón Data visualizations and web development: Jia You Text: Nguyen Khoi Nguyen, Sarah Crespi Photography: The Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at Berkeley Edited by: Catherine Matacic

Citation: Mary Caswell Stoddard, Ee Hou Yong, Derya Akkaynak, Catherine Sheard, Joseph A. Tobias, L. Mahadevan, Science, 2017 DOI:10.1126/science.aaj1945

Special thanks to Sacha Vignieri, Mary Caswell Stoddard, and The Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at Berkeley